Invasive species - a significant driver of extinctions

Betampona Natural Reserve is an eastern lowland rainforest with a high level of faunal and floral biodiversity. Similar to other Malagasy rainforest, Betampona has a high diversity of plant species of which 807 have been identified with 18 believed to be endemic to the Reserve (Dina). Once part of a continuous stretch of rainforest along the east coast of Madagascar, slash and burn agricultural practices have left Betampona an isolated rainforest fragment.

|

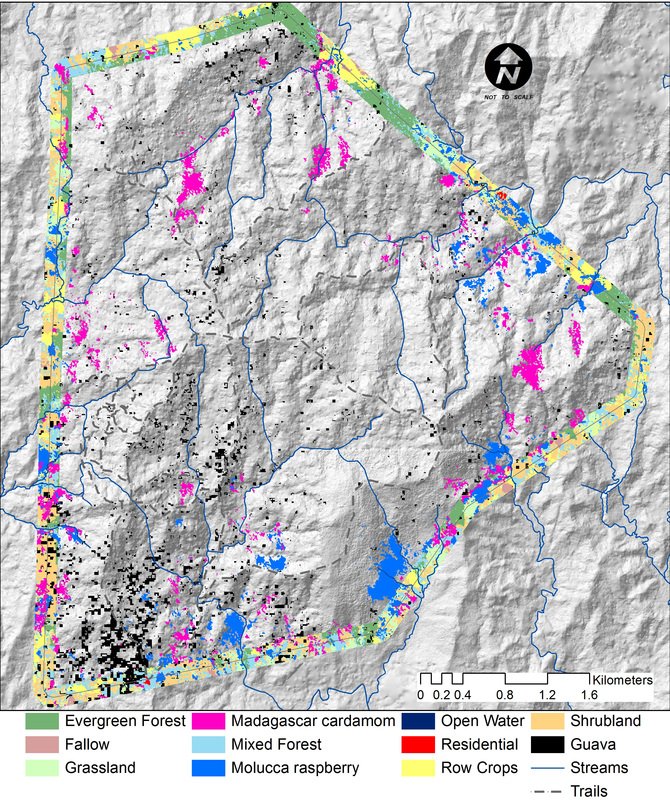

While habitat loss remains the primary cause driving species' extinctions, the problem of invasive species has grown to such an extent that it is now considered to be the second leading cause of extinctions worldwide. Thirteen invasive plant species have been documented to occur in Betampona. The MFG has partnered with Wasit Wulamu, PhD, to monitor the distribution and density through remote sensing technology of Betampona’s three worst invasive plants: strawberry guava, Psidium cattleianum, Madagascar cardamom also called wild ginger, Afromomum angustifolium and Molucca raspberry, Rubus moluccanus. Results show hectares occupied by strawberry guava, wild ginger and Molucca raspberry were 181, 142, and 143.5 hectares respectively. Together they cover a shocking 17.6% of the Reserve.

Strawberry guava is listed as one of the top 100 worst invasive species by the IUCN Invasive Species Specialist Group. It has caused significant ecological damage to forests on the islands of Hawaii, Reunion, Mauritius and Seychelles. Dense thickets form a monoculture by outcompeting native vegetation and thereby change the forest’s structure and species diversity. The IUCN recognizes the extreme threat invasive species represent and have therefore ranked control of invasives as a priority objective for conserving the world's biodiversity. |

IUCN Guidelines for the Prevention of Biodiversity Loss Caused by Alien Invasive Species, 2002.

"When a potentially alien invasive species is first detected, mobilize and activate sufficient resources and expertise quickly". The guidelines recommend total eradication whenever possible but warn that a well designed management plan must be in place because:

"procrastination markedly reduces the chances of success"

The selection of Karen Freeman as Program Manager in 2004 was an auspicious choice. Prior to joining the MFG, Karen had spent five years in Mauritius where she became acutely aware of the negative impact guava exerts on forests and how extraordinarily difficult it is to eradicate it once it has become established. Consequently, her reaction to finding guava within Betampona was to take action. She began by recruiting graduate students to assess the magnitude of guava as well as Madagascar cardamom and Molucca raspberry.

University of Antananarivo graduate student, Yedidya Ratovonamana’s research, which included mapping the distribution of guava in the Reserve, showed that it was not restricted to the forest's edge but had also spread into areas of primary forest. Yididya also established a series of study plots to examine the effect guava had on natural forest regeneration. His results showed quite clearly that guava prevents the majority of native plant seeds from

germinating. That wild pigs (another invasive species) play a role in distributing guava into the Reserve was confirmed by Yididya’s observations of

guava seeds in their feces and matches reports of feral pigs’ prominent role in seed dispersal in Hawaii, Mauritius and other islands. A separate study on the feeding ecology of white-fronted brown lemurs, Eulemur fulvus albifrons, revealed that not only did social groups living in the secondary forest preferentially feed on guava when it came into fruit but so did groups from the primary forest (Toborowsky, 2007). Many lemur species play an important ecological role as seed dispersers of native flora; unfortunately they can also perform that role for invasives.

University of Antananarivo graduate student, Yedidya Ratovonamana’s research, which included mapping the distribution of guava in the Reserve, showed that it was not restricted to the forest's edge but had also spread into areas of primary forest. Yididya also established a series of study plots to examine the effect guava had on natural forest regeneration. His results showed quite clearly that guava prevents the majority of native plant seeds from

germinating. That wild pigs (another invasive species) play a role in distributing guava into the Reserve was confirmed by Yididya’s observations of

guava seeds in their feces and matches reports of feral pigs’ prominent role in seed dispersal in Hawaii, Mauritius and other islands. A separate study on the feeding ecology of white-fronted brown lemurs, Eulemur fulvus albifrons, revealed that not only did social groups living in the secondary forest preferentially feed on guava when it came into fruit but so did groups from the primary forest (Toborowsky, 2007). Many lemur species play an important ecological role as seed dispersers of native flora; unfortunately they can also perform that role for invasives.

A second graduate student, Bernadette Andrianandraina, evaluated the environmental impact and cost of removing guava through manual weeding. She established a series of research plots in Betampona’s Zone of Protection and to assess environmental impact she used number and species of animals and ground temperature as her measured variables. Animals were surveyed through pit trap captures. To obtain the cost of removal she tracked the number of man-hours it took to weed a plot from which a cost/hectare expense was approximated. Her results showed ground temperatures increased and animal species composition changed both in terms of species and numbers after the plots were weeded; more detailed research is required to interpret these results. The labor cost to weed 150 square meters of guava was 72.00 (based on 2007 pay rates). Karen presented copies of both theses, discussed the implications of taking no action and the need for a detailed study in the Reserve with Madagascar National Parks officials. They clearly recognized the serious nature of the threat to Betampona and approved moving forward with guava control trials within the Reserve.

Developing Invasive Weed Control Methods In a Malagasy Rainforest Reserve

|

The proposed study was well suited to serve as a topic for a PhD student and would thereby also serve an MFG and Government of Madagascar objective to increase local capacity to manage the country’s biodiversity. ICTC Manager Lalatahiana (Lala) Randriatavy had a long history with the MFG and had expressed an interest in getting a PhD. When offered the opportunity Lala didn’t hesitate.

The research was designed to evaluate the effectiveness (defined as successful AND causing the least environmental damage), practicality and total cost of four different guava control techniques. Each treatment was applied to three 30mx30m plots in a guava-invaded area of Betampona. The four techniques were: 1) total weeding plots: all guava including roots manually removed; 2) weeding plus reforestation plots: all guava including roots manually removed and plots planted with a selection of native forest trees from the MFG’s nursery; 3) ring-barking plots: bark on all guava stems removed in a 30cm long section and 4) partially cut plots: all leaves and side branches of every guava stem cut. Three control plots (no treatment) were also established. |

Data on environmental variables were collected before treatments began and for 27 months after treatments 1) Daily: ambient and ground temperature and humidity 2) Soil sample analysis for pH, NPK content, conductivity, infiltration, aggregation stability, organic matter content and texture of a 500 gram soil sample, 3) Monthly pitfall measures of species diversity and relative abundance measures for reptiles, amphibians, small mammals and invertebrates. 4) Vegetation structure of each plot and 5) Monthly standardized of photos of all plots.

All four treatment plots were re-weeded of all regenerating guava plants on a quarterly basis. Once a year native and invasive plant regeneration were measured in a 10m x 10m sub-plot located in the center of each treatment plot.

All four treatment plots were re-weeded of all regenerating guava plants on a quarterly basis. Once a year native and invasive plant regeneration were measured in a 10m x 10m sub-plot located in the center of each treatment plot.

The field portion of Lala's research has been completed and he is currently analyzing the data. We will report the results of this important work when it becomes available.