Back to the Wild

Betampona Natural Reserve is a rainforest fully surrounded by farmed and degraded land. When the space between patches is too large or unsafe to cross and the patch is too small to sustain a healthy breeding population, species are subject to the detrimental consequences of inbreeding depression and local extinction. Surveys of Betampona’s lemur populations in 1990 and 1991 were spearheaded by Charlie Welch. Population estimates of the black and white ruffed lemur, Varecia variegata, and the diademed sifaka, Propithecus diadema, were particularly small. The idea to investigate the possibility of a Varecia restocking program was prompted by finding that, compared to densities at other sites, Betampona’s population was lower than expected and V. variegata was the only species that existed in a well-managed captive breeding program.

|

Program Managers Andrea Katz and Charlie Welch began by developing a proposal, in consultation with the Ruffed Lemur SSP, and based on IUCN guidelines. The proposal was submitted to the IUCN and AZA Reintroduction Specialist Groups for their input and, after receiving a majority of positive responses, the MFG Steering Committee approved the project. The goals of the restocking program were: 1) to genetically and demographically reinforce the Betampona ruffed lemur population, 2) contribute to the literature on the science of reintroduction with the first such program for a lemur species, and 3) to increase the level of protection afforded Betampona Natural Reserve through the presence of a research team. This was seen as important because, although Betampona is an officially protected reserve, the actual extent of protection was limited. The Ruffed Lemur SSP developed selection criteria for potential release candidates, including a health evaluation developed by the MFG/Prosimian TAG Veterinary Advisor, and began contacting institutions to gage their willingness to participate in the release program.

A Population Viability Workshop led by Dr. Ulie Seal, Chair of the IUCN Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, was held at Duke Lemur Center in April 1997. Information on wild Varecia populations was based on the available published and unpublished reports and data on the captive population were derived from the International Studbook and experience with the SSP population. The results showed the proposed release of three Varecia groups over a three year period could benefit the survival of the Betampona population, if the animals survived and reproduced. A management strategy of introducing 2 male and 2 female Varecia at 10 year intervals (once per generation) was shown to decrease the risk of extinction, increase population growth and improve retention of average genetic heterozygosity (more than 90%). |

After a selection process that excluded some individuals from consideration, the final candidates were transferred to one of two institutions that had large free-ranging facilities, referred to as "boot camp": St. Catherine's Wildlife Survival Center and Duke Lemur Center. Boot camp provided zoo-bred individuals with the opportunity to experience a natural and much more complex environment and thereby adjust and improve locomotor skills, develop behavioral responses to changing weather conditions and to potential predators.

Throughout this time, the Program Managers communicated extensively with the Ministry of the Environment. The MFG’s Protocol of Collaboration with the Government of Madagascar included assisting them with endangered species conservation and this project was consistent with this objective. To further reinforce the MFG / Madagascar Government partnership, a specific Protocol of Collaboration for the restocking program was developed. Grants

and other funds were raised to cover the project's expenses.

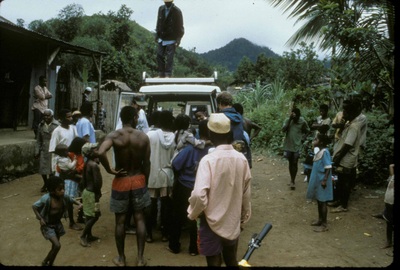

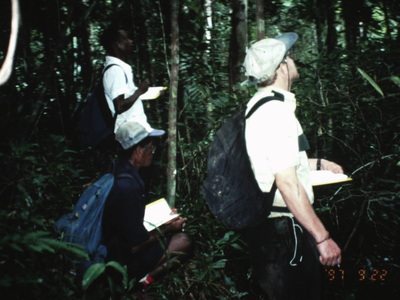

The first candidates chosen for the release were three males (Zuban Ubi, Janus and Sarph) and two females (Praesepe and Latitia), who were born and raised at Duke Lemur Center. The five were judged as the best candidates for the first releases as they were already a cohesive family group with substantial free-ranging experience. On October 17, 1997 the “Carolina Five” as nicknamed by John Cleese in the BBC Special Back to the Wild which he starred, were placed in crates and, accompanied by San Francisco Zoo veterinarian Graham Crawford, sent on the long journey to their native homeland. They were met at the Antananarivo airport by Charlie Welch for the drive to Toamasina and eventually to Fotsimavo where the road ends. Dr. Adam Britt, who would lead the research team, met his study subjects and accompanied them on the 90 minute hike to Rendrirendry where they were released into a temporary habituation cage The lemurs were maintained on their normal Purina monkey biscuit diet while being introduced to Varecia food items gathered from the forest.

and other funds were raised to cover the project's expenses.

The first candidates chosen for the release were three males (Zuban Ubi, Janus and Sarph) and two females (Praesepe and Latitia), who were born and raised at Duke Lemur Center. The five were judged as the best candidates for the first releases as they were already a cohesive family group with substantial free-ranging experience. On October 17, 1997 the “Carolina Five” as nicknamed by John Cleese in the BBC Special Back to the Wild which he starred, were placed in crates and, accompanied by San Francisco Zoo veterinarian Graham Crawford, sent on the long journey to their native homeland. They were met at the Antananarivo airport by Charlie Welch for the drive to Toamasina and eventually to Fotsimavo where the road ends. Dr. Adam Britt, who would lead the research team, met his study subjects and accompanied them on the 90 minute hike to Rendrirendry where they were released into a temporary habituation cage The lemurs were maintained on their normal Purina monkey biscuit diet while being introduced to Varecia food items gathered from the forest.

The lemurs were maintained on their normal Purina monkey biscuit diet while being introduced to Varecia food items gathered from the forest. Graham carried out a second veterinary exam during which each individual was fitted with a radio collar. After receiving a clean bill of health, the five were moved to a second cage within the Reserve. On the 10th of November, the Carolina Five were released into the forest.

ZubenUbi and Praesepe remained a pair when released into Betampona. In October 1998, Praesepe constructed and remained in a nest for several days before abandoning it. The nest was too high for the staff to check but it is likely that she had given birth to young that did not survive. A year later she gave birth to triplets which the pair successfully raised through weaning. One infant disappear in April and another in July, however, the third, a male name Faly is believed to still be alive. Praesepe was found dead in July 2000 of unknown causes although predation was ruled out. After her death, ZubenUbi and Faly traveled together until ZubenUbi died in October 2000.

Letitia was the first member of the group to die. Her skeletal remains were found three months after the group had been released. The tooth marks on her skull suggested she had most likely been killed by a fossa. After eight months in the forest, Janus was found dead with a broken neck; the team felt it was probably the result of a fall.

Sarph lived for over ten years. His short tail, resulting from an injury he sustained when young, made him very distinctive and easy to identify. In October 1998 he was recaptured and paired with a female,Trisha, from the second release group. In December 1998 he disappeared for so long it was assumed he had died thus the team was overjoyed to find him 11 months later fully integrated into a wild group. In October 2001 Sarph was seen with a wild female and her infant. This trio was sometimes observed with two other adults. In early 2007 Sarph was seen with a female and her October 2006 offspring. Sarph's home range was an area of Betampona called Vohitsivalana until March 2008; the team noted that a new male had joined the small group in Vohitsivalana. October 14th was the last day any of the agents observed Sarph; that day he was observed with a female far outside of his normal home range.

The second release group included one male and three females. Barney, a male born at the Los Angeles Zoo, was transferred to St. Catherine’s and paired with Tricia, a female with 15 months of free-ranging experience. Barney spent three months in boot camp before his transfer to Madagascar. Born at Utah’s Hogle Zoo, sisters, Dawn and Jupiter, spent two months at Duke “boot-camp” before they were transferred to Madagascar. For the release, Sarph a male from the 1997 release, was recaptured and paired with Trisha to form one group. The pair was released in late November and remained together for a few weeks until Sarph disappeared in December. Tricia remained in the area until March when she traveled to the northwest area of Betampona and was last seen close to the border. She was never seen again and no radio signals were received.

Barney, Dawn and Jupiter were released together as a second group and rarely left the vicinity of their release site. Although provisioned food was presented off the ground, all three of these individuals spent too much time on the ground. Jupiter was killed by a fossa in May 2000; when Barney succumbed to fossa predation in November 2000, the decision was made to immediately capture Dawn and bring her back into captivity. Dawn was taken to the Ivoloina Zoo where she lived another ten years and at age 15 gave birth to her first litter (bottom right photo of Dawn and her offspring).

Barney, Dawn and Jupiter were released together as a second group and rarely left the vicinity of their release site. Although provisioned food was presented off the ground, all three of these individuals spent too much time on the ground. Jupiter was killed by a fossa in May 2000; when Barney succumbed to fossa predation in November 2000, the decision was made to immediately capture Dawn and bring her back into captivity. Dawn was taken to the Ivoloina Zoo where she lived another ten years and at age 15 gave birth to her first litter (bottom right photo of Dawn and her offspring).

For the third release a female, Hale, from the Santa Ana Zoo and Bopp, a male born at Memphis, were sent to Duke boot camp in 1997. The pair bred and produced a single male in 1999 and twin males in 2000. Bopp died in April 2000 before he could accompany his mate and their three male offspring, Kintana, Tany and Masoandro to Madagascar in November 2000. The four were released into the Reserve in January 2001. She and her three sons remained as a group and adjusted well to the wild. The young males were noted to travel more agilely in the forest undoubtedly helped by their lower body weight and early experience at boot camp. Hale did not come into estrus in December/January, the normal season in the northern hemisphere, nor did it appear she did so in June/July, the normal season in the southern hemisphere. However the following breeding season she was joined by a wild male and the group of five traveled together until Hale gave birth to a litter of two in October 2002. The pair and their offspring, a male and female, formed a group of four. Hale died in September 2003, another victim of fossa predation.

Kintana and his two younger brothers, Tany and Masoandra, moved north and although the team was able to locate the two younger males, Kintana disappeared. The brothers were joined by a wild male and the three traveled extensively in the northwest quadrant of the Reserve. In the summer of 2003 the team noted that the three males could occasionally be found traveling with Hale, her mate and two offspring. This pattern continued even after Hale's death.

Kintana and his two younger brothers, Tany and Masoandra, moved north and although the team was able to locate the two younger males, Kintana disappeared. The brothers were joined by a wild male and the three traveled extensively in the northwest quadrant of the Reserve. In the summer of 2003 the team noted that the three males could occasionally be found traveling with Hale, her mate and two offspring. This pattern continued even after Hale's death.

|

The Betampona team has labeled the two groups: Group 3A = Hale's wild mate and their 2002 offspring, male Tselatra and female Volana; Group 3B = Tany, Masosandra and a wild male. In 2006 Tany and Masoandra were found with a female and infant. Beginning in 2007 the two brothers were sometimes observed in separate subgroups of two and over the years they have been joined by other ruffed lemurs while Group 3A and 3B continue to merge from time to time. Tany and Masosndra have been observed near females with offspring. We cannot assert that any of the released males (with the exception of ZubenUbi) have sired offspring. To date, we have not collected a sufficient number of genetic samples from the population to confirm paternity.

|

Publications from the Black and White Ruffed Lemur Restocking Program

Welch, C. R.; Katz, A. S. (1992). Survey and census work on lemurs in the natural reserve of Betampona in eastern Madagascar with a view to reintroductions. DODO, Journal of the Wildlife Preservation Trusts 28: 45-58.

Junge, RE; Garrell, D. (1995). Veterinary Evaluation of ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata) in Madagascar. Primate Conservation 16:44-46, 1995.

Junge, R.E. (1996). The significance of infectious diseases on reintroduced populations – medical evaluation procedures of Varecia to be released at Betampona. Lemur News 2: 11

Welch, C. (1996). Projects at Ivoloina and Betampona in eastern Madagascar. Lemur News 2: 11

Britt, A. (1998). Effects of a naturalistic environment on the feeding and locomotor behaviour of captive-bred Varecia variegata variegata. Folia Primatologica 69 (Suppl. 1): 407- 408.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (1998). The first release of captive-bred lemurs into their natural habitat. Lemur News 3: 8 -11.

Britt, A. (1998). Encouraging natural feeding behavior in captive-bred black and white ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata variegata). Zoo Biology 17: 379 - 392.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (1999). Re-stocking of Varecia variegata variegata: the first six months. Primate Eye 67: 36 - 39.

Britt, A. (1999). Encouraging natural feeding behaviour in captive Varecia variegata variegata: the first six months. Laboratory Primate Newsletter 38(2): 19 - 20.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (1999). Re-stocking of Varecia variegata variegata: the first six months. Laboratory Primate Newsletter 38(2):

20 - 22.

Britt, A. (2000). Diet and feeding behaviour of the black and white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata variegata) in the Betampona Reserve, Eastern Madagascar. Folia Primatologica 71: 133 - 141.

Britt, A.; Katz, A.; Welch, C. (2000). Project Betampona: Conservation and Re-stocking of Black and White Ruffed Lemurs (Varecia variegata variegata). In: T. L. Roth, W. F. Swanson & L. K. Blattman (eds.) Proceedings of the Seventh World Conference on Breeding Endangered Species,

May 22 - 26 1999, Cincinnati, Ohio:87 - 94

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (2000). Ruffed Lemur re-stocking and conservation program update. Lemur News 5:36 - 38.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (2001). The impact of Cryptoprocta ferox on the Varecia variegata variegata re-stocking project at Betampona. Lemur News 6: 35 - 37.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (2002). The release of captive-bred black and white ruffed lemurs into the Betampona Reserve, eastern Madagascar. IUCN

Reintroduction News 21: 18-20.

Britt, A. (2002). Seasonal behavioural variation in Varecia variegata variegata at Betampona Natural Reserve, Madagascar. [Abstract]. Am J. Primatology 57 (suppl 1):28.

Junge, R.; Lewis, E. (2002). Medical evaluation of free-ranging primates in Betampona Reserve, Madagascar. Lemur News 7:23-25

Sargent, E.L.; Anderson, D. The Madagascar Fauna Group (2003). In S. Goodman & J. Benstead (eds.) The Natural History of Madagascar. Univ. of Chicago Press:1543-1545

Britt, A.; Iambana, B.R.; Welch, C.R.; Katz, A.S. (2003). Project Betampona: Re-stocking of Varecia variegata variegata into the Betampona Reserve. In S. Goodman & J. Benstead (eds.) The Natural History of Madagascar. Univ. of Chicago Press:1545-1551.

Britt, A.; Iambana, B.R. (2003). Can captive-bred Varecia variegata variegata adapt to a natural diet on release to the wild? International Journal of Primatology 24(5): 987-1005.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (2003). Can small, isolated primate populations be effectively reinforced through the release of individuals from a captive population? Biological Conservation 15: 319-327

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (2003). Project Betampona Update Lemur News 8:6

Rabesandratana, A.Z. (2003). Comparative studies of foraging behaviour of released and feral Varecia variegata variegata (Kerr 1792) in the Integral Natural Reserve of Betampona. Lemur News 8: 30.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A.; Iambana, B.; Porton, I.; Junge, R.; Crawford, G.; Williams, C; Haring, D. (2004). The re-stocking of captive bred ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata variegata) into the Betampona Reserve: methodology and recommendations. Biodiversity and Conservation 13: 635-657.

Junge, R.E.; Louis, E.E. (2005). Preliminary biomedical evaluation of wild ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata and V. rubra). American Journal of Primatology 66 (1):85-94.

Dickie, L. (2006) Madagascar Fauna Group: an integrated approach to conservation. Proceedings of the EAZA Conference 2005, Bristol, 6-10 September 2005. Hiddinga, B. (ed) Amsterdam: EAZA:186-190.

Durrell, L; Anderson, D.; Katz, A.S.; Gibson, D.; Welch, C.R.; Sargent, E.L.; Porton, I. (2007). The Madagascar Fauna Groupo: what zoo cooperation can do for conservation. In: Zoos in the 21st Century. Zimmerman, A., Hatchwell, M., Dickie, L., West, C. (eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK: 275-286.

Britt, A.; Welch,C.; Katz, A.; Freeman, K. (2008). Supplementaion of the black and white ruffed lemur population with captive-bred individuals in Betampona Natural Reserve. In: Global Re-Introduction Perspectives: Re-Introduction Case Studies from Around the Globe. Soorae, P.S. (ed). Abu Dhabi: IUCN Re-Introduction Specialist Group:197-201.

Schmidt, D. A.; Iambana’ R.B.; Britt, A.; Junge, R.E.; Welch, C.R.; Porton, I.J.; Kerley, M.S. (2009). Nutrient composition of plants consumed by black and white ruffed lemurs, Varecia variegata, in the Betampona Natural Reserve, Madagascar. Zoo Biology 28: 1–22.

Porton, I.; Freeman, K. (2010). The Madagascar Fauna Group: zoos working together do make a difference. In: G. Dick and M Gusset, (Eds). Building a

Future for Wildlife, Zoos and Aquariums Committed to Biodiversity Conservation. WAZA. Gland, Switzerland. 139-144.

Freeman, K.L.M., Bollen, A., Solofoniaina, F.J., Andriamiarinoro, H., Porton, I., Birkinshaw, C.R. (2014). The Madagascar Fauna and Flora Group as an example of how a consortium is enabling diverse zoological and botanical gardens to contribute to biodiversity conservation in Madagascar. Plant Biosystems 148 (3): 570-580. DOI: 0.1080/11263504.2014.900125

Junge, RE; Garrell, D. (1995). Veterinary Evaluation of ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata) in Madagascar. Primate Conservation 16:44-46, 1995.

Junge, R.E. (1996). The significance of infectious diseases on reintroduced populations – medical evaluation procedures of Varecia to be released at Betampona. Lemur News 2: 11

Welch, C. (1996). Projects at Ivoloina and Betampona in eastern Madagascar. Lemur News 2: 11

Britt, A. (1998). Effects of a naturalistic environment on the feeding and locomotor behaviour of captive-bred Varecia variegata variegata. Folia Primatologica 69 (Suppl. 1): 407- 408.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (1998). The first release of captive-bred lemurs into their natural habitat. Lemur News 3: 8 -11.

Britt, A. (1998). Encouraging natural feeding behavior in captive-bred black and white ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata variegata). Zoo Biology 17: 379 - 392.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (1999). Re-stocking of Varecia variegata variegata: the first six months. Primate Eye 67: 36 - 39.

Britt, A. (1999). Encouraging natural feeding behaviour in captive Varecia variegata variegata: the first six months. Laboratory Primate Newsletter 38(2): 19 - 20.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (1999). Re-stocking of Varecia variegata variegata: the first six months. Laboratory Primate Newsletter 38(2):

20 - 22.

Britt, A. (2000). Diet and feeding behaviour of the black and white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata variegata) in the Betampona Reserve, Eastern Madagascar. Folia Primatologica 71: 133 - 141.

Britt, A.; Katz, A.; Welch, C. (2000). Project Betampona: Conservation and Re-stocking of Black and White Ruffed Lemurs (Varecia variegata variegata). In: T. L. Roth, W. F. Swanson & L. K. Blattman (eds.) Proceedings of the Seventh World Conference on Breeding Endangered Species,

May 22 - 26 1999, Cincinnati, Ohio:87 - 94

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (2000). Ruffed Lemur re-stocking and conservation program update. Lemur News 5:36 - 38.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (2001). The impact of Cryptoprocta ferox on the Varecia variegata variegata re-stocking project at Betampona. Lemur News 6: 35 - 37.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (2002). The release of captive-bred black and white ruffed lemurs into the Betampona Reserve, eastern Madagascar. IUCN

Reintroduction News 21: 18-20.

Britt, A. (2002). Seasonal behavioural variation in Varecia variegata variegata at Betampona Natural Reserve, Madagascar. [Abstract]. Am J. Primatology 57 (suppl 1):28.

Junge, R.; Lewis, E. (2002). Medical evaluation of free-ranging primates in Betampona Reserve, Madagascar. Lemur News 7:23-25

Sargent, E.L.; Anderson, D. The Madagascar Fauna Group (2003). In S. Goodman & J. Benstead (eds.) The Natural History of Madagascar. Univ. of Chicago Press:1543-1545

Britt, A.; Iambana, B.R.; Welch, C.R.; Katz, A.S. (2003). Project Betampona: Re-stocking of Varecia variegata variegata into the Betampona Reserve. In S. Goodman & J. Benstead (eds.) The Natural History of Madagascar. Univ. of Chicago Press:1545-1551.

Britt, A.; Iambana, B.R. (2003). Can captive-bred Varecia variegata variegata adapt to a natural diet on release to the wild? International Journal of Primatology 24(5): 987-1005.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (2003). Can small, isolated primate populations be effectively reinforced through the release of individuals from a captive population? Biological Conservation 15: 319-327

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A. (2003). Project Betampona Update Lemur News 8:6

Rabesandratana, A.Z. (2003). Comparative studies of foraging behaviour of released and feral Varecia variegata variegata (Kerr 1792) in the Integral Natural Reserve of Betampona. Lemur News 8: 30.

Britt, A.; Welch, C.; Katz, A.; Iambana, B.; Porton, I.; Junge, R.; Crawford, G.; Williams, C; Haring, D. (2004). The re-stocking of captive bred ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata variegata) into the Betampona Reserve: methodology and recommendations. Biodiversity and Conservation 13: 635-657.

Junge, R.E.; Louis, E.E. (2005). Preliminary biomedical evaluation of wild ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata and V. rubra). American Journal of Primatology 66 (1):85-94.

Dickie, L. (2006) Madagascar Fauna Group: an integrated approach to conservation. Proceedings of the EAZA Conference 2005, Bristol, 6-10 September 2005. Hiddinga, B. (ed) Amsterdam: EAZA:186-190.

Durrell, L; Anderson, D.; Katz, A.S.; Gibson, D.; Welch, C.R.; Sargent, E.L.; Porton, I. (2007). The Madagascar Fauna Groupo: what zoo cooperation can do for conservation. In: Zoos in the 21st Century. Zimmerman, A., Hatchwell, M., Dickie, L., West, C. (eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK: 275-286.

Britt, A.; Welch,C.; Katz, A.; Freeman, K. (2008). Supplementaion of the black and white ruffed lemur population with captive-bred individuals in Betampona Natural Reserve. In: Global Re-Introduction Perspectives: Re-Introduction Case Studies from Around the Globe. Soorae, P.S. (ed). Abu Dhabi: IUCN Re-Introduction Specialist Group:197-201.

Schmidt, D. A.; Iambana’ R.B.; Britt, A.; Junge, R.E.; Welch, C.R.; Porton, I.J.; Kerley, M.S. (2009). Nutrient composition of plants consumed by black and white ruffed lemurs, Varecia variegata, in the Betampona Natural Reserve, Madagascar. Zoo Biology 28: 1–22.

Porton, I.; Freeman, K. (2010). The Madagascar Fauna Group: zoos working together do make a difference. In: G. Dick and M Gusset, (Eds). Building a

Future for Wildlife, Zoos and Aquariums Committed to Biodiversity Conservation. WAZA. Gland, Switzerland. 139-144.

Freeman, K.L.M., Bollen, A., Solofoniaina, F.J., Andriamiarinoro, H., Porton, I., Birkinshaw, C.R. (2014). The Madagascar Fauna and Flora Group as an example of how a consortium is enabling diverse zoological and botanical gardens to contribute to biodiversity conservation in Madagascar. Plant Biosystems 148 (3): 570-580. DOI: 0.1080/11263504.2014.900125